Limited availability of building materials, access solely to domestic technologies and prefabrication developed through makeshift efforts—this is the shared vocabulary of Poland’s post-war architecture. Nevertheless, it allowed to construct buildings whose forms and spatial solutions were often unique.

Terracotta available in just a handful of colours, mosaics from factory waste, terrazzo floorings, laminated boards, characteristic grooved aluminium panels on the façades, bars and railings whose metalwork resembled crude steelwork. These elements, due to their semi-handmade production methods, are impossible to be copied nowadays. When a post-war object is saved from demolition, its renovation is usually connected with replacing old materials with modern ones. New materials are devoid of the aura of authenticity. Once introduced into a building, they completely change its expression.

Most of socmodernist buildings fell down after the accusation of their poor technical condition. Relying on the limited palette of materials made with semi-artisanal methods that only imitated mass-produced building components, they are indeed difficult to renovate with contemporary products. However, the same elements can be found in other buildings from the same period. Materials form a shared vocabulary that defines those buildings as the subjects of the same species. Such affinity opens the field for architectural transplantations—by donations of material tissue, defunct socmodernist buildings can save their architectural relatives.

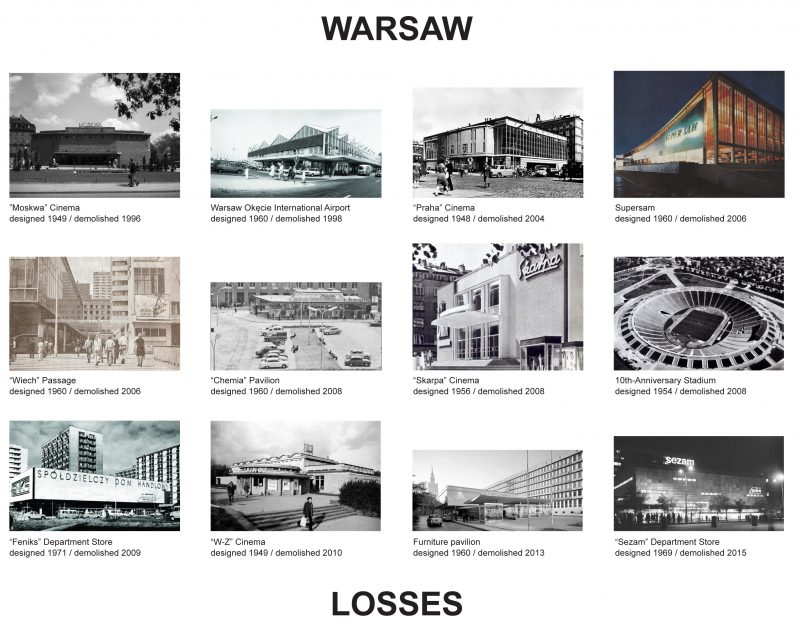

In Warsaw, where the appreciation of whatever is left from post-war modernistm falls behind the speed of changes in the urban fabric, extending the range of architectural transplantations to cover other cities may become a way of repaying Warsaw’s architectural debt. The reconstruction of Poland’s capital after WWII was possible largley due to transports of bricks from ruined historical monuments from all over the country, espacially from the socalled Recovered Territories in the west. Now the debt can be repaired—elements of constructions that couldn’t be saved from demolition may contribute to sustaining the lives of modernist objects in other cities—and thus symbolically survive, although outside Warsaw.

Meticulous inventorying, documentation of architectural details and,when demolition becomes inevitable—depositing fragments of the building in other constructions seems to be better than losing these constructions forever. Even after being separated from the original building, its elements retain the memory of the place, and having been transplanted onto other structures, they may save the lives of surviving members of the architectural family.

Curtain wall construction post

Curtain wall from Warszawa Powiśle station, designed by Arseniusz Romanowicz, Piotr Szymaniak, 1954–1963 & door handles from the shop vitrine of the modernist building at Chłodna 25 Street in Warsaw. Photo Kuba Rodziewicz/RZUT, 2019

Since Walter Gropius’ projects, such as the Fagus factory in Alfeld or the Bauhaus school in Dessau, wall made of curtains have often come to symbolize modernism. Devoid of any load-bearing function, they serve as thermal and functional partition and provide interiors with daylight. In communist Poland, it was difficult to build them due to material shortages. For this reason, in Polish post-war architecture the skeleton of the glass elevation was often made from flat bars, which made it possible to create imitations of curtain walls in spite of the small size of the glass panes.

Acoustic and aluminium panels

Acoustic panels & grooved aluminium panels from Warszawa Wschodnia station, designed by Arseniusz Romanowicz, Piotr Szymaniak, 1955. Photo Kuba Rodziewicz/RZUT, 2019

Acoustic panels made from hardboard and gypsum and covered with oil paint were laid on ceilings in order to ensure the proper acoustics.

Grooved aluminium panels were often used to finish the elevations of modernist pavilions. Placed one next to another and linked by tongue and groove joints, they constituted a continuous frieze that highlighted the divisions of the elevation. Until recently, similar panels could be seen on the elevation of the Emilia pavilion (demolished in 2016); they are still visible on the building of the headquaters of the Association of Polish Architects in Warsaw (SARP) or the Auditorium of the Faculty of Chemistry of Wrocław University. It’s usually enough just to clean them in order to restore their old splendour.

Train station clocks

Train station clocks; stone windowsill from Warszawa Wschodnia station, designed by Arseniusz Romanowicz, Piotr Szymaniak, 1955. Photo Kuba Rodziewicz/RZUT, 2019

Train station clocks were produced by thxe A-6 Precision Instruments Factory in Szczecin, a state-owned plant opened in 1960 as part of a programme of professional activation of women in the Western Borderland. Their characteristic faces used to be a permanent feature of Polish railway stations. However, as the stations are renovated, these interesting mechanisms with a graphical appearance are gradually replaced with digital clocks.

Floor tile

The recently demolished Emilia pavilion in Warsaw, whose main asset was its spatial embedding in the unfinished project of the so-called West Wall and the nearby housing estate, boasted many interesting material solutions. Among them was the floor. Its tiles were made from light cement and mostly white grit. Consequently, the floor reflected light and illuminated the interior of the pavilion.

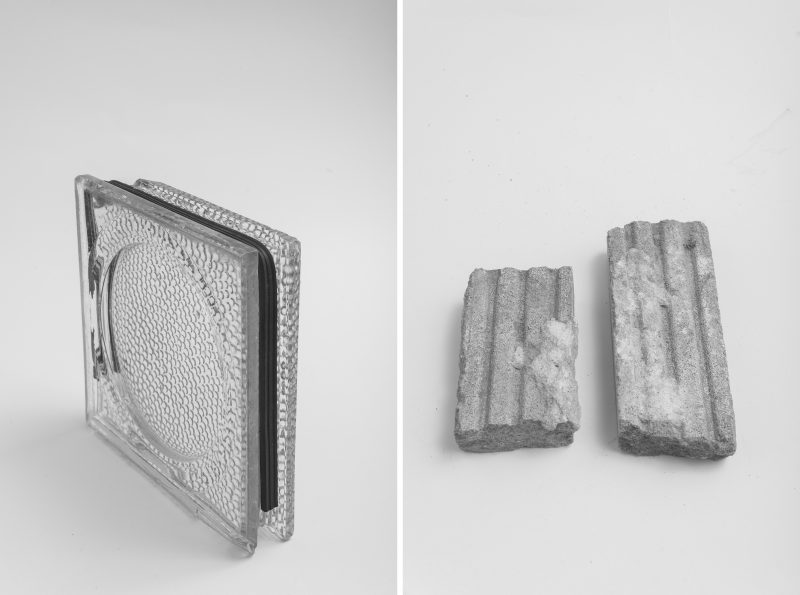

Glass bricks

Glass bricks & brics from Warszawa Stadion station, designed by Arseniusz Romanowicz, Piotr Szymaniak, 1955. Photo Kuba Rodziewicz/RZUT, 2019

Glass bricks, used for building or filling in walls and ceilings or as decorative elements providing interiors with daylight (due to their light transmittance of up to 60%), were made in several shapes, most often square (like the ones presented in the Chemistry Auditorium) or circular. As a building material, glass bricks were fixed together in a way similar to ordinary bricks, with mineral wool used to fill in the joints between them. In some projects, they were cast into a reinforced concrete gridwork.

Terracotta tiles mosaic

Textile and terracotta tiles mosaic from Warszawa Powiśle station, designed by Arseniusz Romanowicz, Piotr Szymaniak, 1954–1963 and Warszawa Stadion station, designed by Arseniusz Romanowicz, Piotr Szymaniak, 1955. Photo Kuba Rodziewicz/RZUT, 2019

Mosaics consisting of terracotta tiles were often used as finishing material in the modernist architecture from the mid-1950s to the 1970s. Available in just a handful of colours and sizes, they were used to finish elevations, walls and floors inside buildings. A similar mosaic constituted the décor of the Chemistry Pavilion (demolished in 2008), the Supersam (demolished in 2006) or the Hungarian Trade Agency, which is deteriorating in Warsaw.

History of the project

The research was first presented as a competition entry by CENTRALA for the Taking Buildings Down competition organized by the Storefront for Art and Architecture, 2016.

The concept was tested for the first time during Survival Art Review (23–27 June 2017) when the collection was introduced into the building from the same period—the Auditorium of the Faculty of Chemistry of the Wrocław University of Technology—as temporary spolia. The presentation entitled Post-war Modernism Album was based on subtle interventions in the architectural fabric of the auditorium. with use of original components such as the Emilia pavilion in Warsaw or Warsaw-East railway station, which constitute a repository of knowledge about the material dimension of a vanishing architectural layer of Polish cities.

The collection was first presented in the ephemeral Institute for Spatial Management (noteworthy) in frame of Synchronicity 2016: Unbalanced Architecture (27 November–16 December 2016) organized by Bęc Zmiana Foundation.

Re-use of architecture shared vocabulary: Post-war Modernity Album posters was presented in Kharkiv School of Architecture, Kharkiv, September 2017

Further reading

Architectural Transplantations, competition entry for Taking Buildings Down competition organized by Storefront for Art and Architecture, February 2016 (pdf link)

Architectural Transplantations, article in “Kultura Liberalna”, 2016 no. 375 (in Polish only); reprinted in “ERA 21”, 2019 no. 6 (in Czech only)

Post-war Modernism Album, CENTRALA and Aleksandra Kędziorek [in:] Survival 15 / 201, ed. Bieniek, Michał, Art Transparent, Wrocław 2017

Atlas Polskiego Modernizmu, CENTRALA, “RZUT +21: STAROŚĆ”, 2019 no. 3 (in Polish only)

Video lecture Konserwacja powojennego modernizmu by CENTRALA at the Tu było, tu stało Facebook, 2020